Look! A cat!

No, seriously. Have you ever really looked at one of these before?

The kitty doesn’t have to be Fluffy, although house cats are a lot easier to study at home than, say, mountain lions or tigers.

Believe it or not, apart from size and a few lifestyle-related anatomical details, you do have a little mountain lion/tiger there!

The essence of Cat is not so easy to describe. (Image: Olas, CC BY-SA 2.0)

That’s because all members of family Felidae are built alike. (Turner and Anton)

What is a cat?

This information is from Kitchener et al., Wright and Walters, and some fun hours spent watching house cats — my own and friends’ cats.

The long feline body is much more supple than that of a gray wolf (Fido’s closest relative; I use wolves for comparison because dogs have been domesticated longer and in many cases don’t look much like their forebear now; outside the show ring, Fluffy still resembles its African wildcat ancestor in many ways).

Cats do some amazing contortions while chasing prey, climbing, fighting, or falling, including this:

Their powerful legs aren’t quite as long or thin as a wolf’s, although cats still accelerate quickly and can speed across short distances (a wolf pack runs dinner down, while a hungry cat sneaks up on and jumps its prey, which either escapes or doesn’t get very far).

The cheetah has its own hunting style, of course, as we’ll see later on.

Generally speaking, the cat’s sturdy leg ends in a deceptively smooth paw that conceals very sharp hook-like claws on every digit except the two “thumbs.”

The claws spring out of their protective sheaths like switchblades when a cat reaches out, spreading its digits. (Image: Fabian via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Yes, cats have a thumb, though it doesn’t move like ours does. There are five digits on each front paw and four on the hind foot (unless Fluffy has one of those adorable and harmless polydactyly mutations).

Can you see part of the thumb in that image above?

There’s a “thumb nail” but it isn’t concealed. We call it a dew claw. It doesn’t need a protective sheath because it never touches the ground.

Cheetahs are the exception again. Not in terms of thumbs (which they have and skillfully use, as we’ll soon see), but because their claws never fully retract.

The sharpness wears off, but those exposed “cleats” give this racing cat excellent traction.

Not shown: a wolf-like muzzle. Yet dogs, cats, and all other members of the order Carnivora have the same meat-processing cheek teeth, called carnassials. (Image:

Jaroslaw Pocztarski, CC BY 2.0.

The head is another distinguishing feline feature. It’s more or less rounded, depending on species.

Cats have proportionately huge eyes, as well as a very blunt face compared to the pointed muzzles on wolves and many other caniform predators.

Why are cats built like this?

Well, exploring that question is the whole purpose of this series. Let’s ease into it with a quick look at a few of Dem Bones — the building blocks of all vertebrates (animals with their hard parts on the inside).

Why?

- We can relate to cats because their skeletons are like ours in some ways.

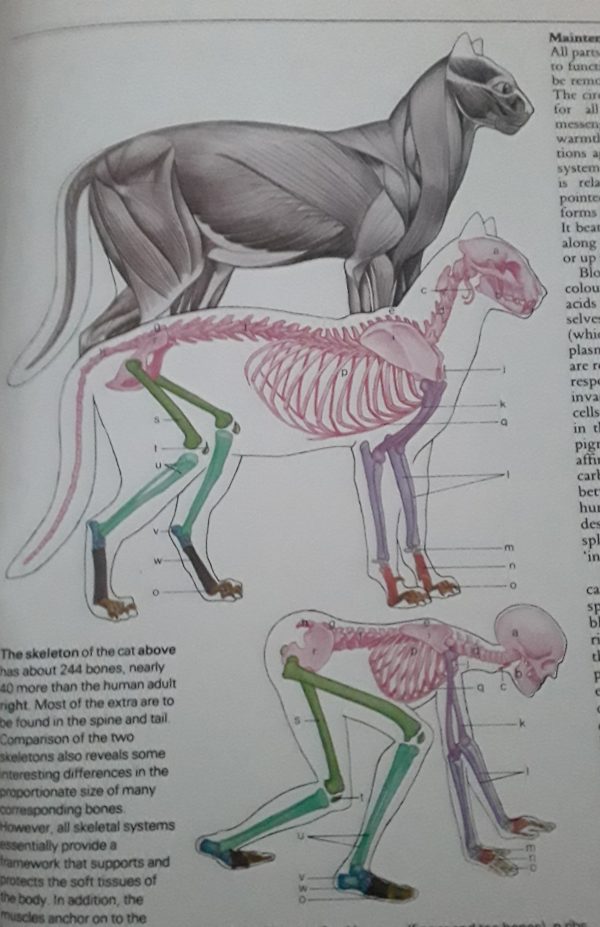

In this diagram, for example, the same bones in cat and human are the same color, but evolution has changed their shapes. (Don’t worry — there’s no quiz, but please do note the purple bones in the hind paws/feet and the red bones in the front paws/hands, because the cheetah video coming up explains why those bones lengthened so dramatically in cats!)

We’ve gotten down on the floor to play with Fluffy lots of times, but who would have thought that we could learn more about our pet in that position? (Image: The graphic is from one of my references; I’m reproducing it here because everyone who is curious about house cats should know about “The Book of The Cat,” edited by Michael Wright and Sally Walters, even though it’s more than forty years old. In many ways, it’s a timeless resource.)

- In skeletons, the effects of evolution show up in surprising ways.

- Any history of cats must include fossils, which are usually bones and teeth. Paleoartists study the anatomy of modern cats and then apply what they’ve learned to fossils in order to reconstruct long-extinct cats.

Such experts can read the subtleties. They spot clues that suggest how animals lived. For instance, Kitchener et al. discuss how different the shoulder blades look in a cat that can climb (the leopard) and in a cheetah, which can’t climb.

But that’s way more detail than we need to get into. It might seem irrelevant, too, since we also see leopards in trees and cheetahs living at ground level.

Those clues matter a lot, though, when you’re trying to understand what extinct cats like cave lions and sabertooths were like.

Carnivora

At this point in the series, all we really need to …

Note the dog’s longer muzzle and thinner leg bones, compared to cats. Compared to us, though, dog and cat skeletons are similar. Of course: they’re carnivorans (part of the order Carnivora). Our own Primate ancestors took a different path, and that really shows up in our bones. (Image: Bianca Van Dijk/Pixabay)

Wait. Is that barking?

Sigh.

It’s getting to be a regular Halloween Park around here.

Still, the dog-cat thing is an important part of the story of how cats evolved.

In fact, the whole order Carnivora is split in two, with part of the predators being dog-like (caniform) and the others cat-like (feliform).

Meerkats, for example, are feliforms, though they’re not true cats. Bears, with their wolf-like muzzles are definitely caniforms, but it might surprise you to learn that barking hyenas are feliforms!

And in the distant past lived creatures like beardogs and barbourofelids — but let’s not get into all that yet. There’s so much, it would be overwhelming.

Let’s just watch a cheetah video.

I like this one because:

- They clearly explain, in simple terms and using a comparison to people, how a cheetah works. Since cheetahs, although extreme in some ways, are a lot like any other cat, this video brings to life that graphic we saw earlier.

- In particular, it shows how the longer paw bones give cheetahs and other cats more acceleration and speed.

- Starting around 4:15 they describe the dew claw and show the cat reaching out and using it to bring prey down.

One thing, though.

The animation shows those paw bones stretching out, but of course individual cats didn’t really go through the sort of torture David Naughton’s character suffered in that grisly scene in An American Werewolf in London.

Little changes working on animal populations over vast periods of time did it.

But before we can even start to see how that could happen, we need to get some sort of a handle on geologic time.

Time analogies

The hills aren’t really eternal, and that’s mind-bending, if you aren’t used to geological calendar terms like ‘Ma,’ and names that end in ‘-cene’ — for instance, “the first cat appeared around 20 Ma, during the early Miocene.”

A sentence like that is a guaranteed snorer unless the reader has something familiar as a reference point.

Saying “a cat raced across the baseball field at 8 p.m., during the sixth inning” has a lot more general appeal to it.

This is something cats do. There are actually compilations of these episodes online, but the poor little thing is usually terrified. This one seems more feisty.

While chasing cats across the evolutionary “field,” we’ll have a sort of calendar in our heads to keep ourselves oriented. It uses a shorthand I came up with by twisting real scientific terms like mega-annum (Ma) into something that was still accurate but a little easier for a layperson to grasp.

It was more of a survival technique to help me get 65 million years of history into perspective than a conscious decision, but it really works.

Once you can see ‘Ma,’ its relative ‘Ka,’ and the geological-period names, especially those ending in ‘-cene,’ as calendar terms, that first sentence up above — “the first cat appeared around 20 Ma, during the early Miocene” — is just as exciting as the one about baseball.

Why?

Because this little Miocene cat joined the “game” and helped win it (that is, cats are still around while the big-leaguers of those days, like bear-dogs and sabertoothed cat-like barbourofelids, are long gone).

Where did that cat come from, and how did it evolve?

These are very tough and not yet fully answered questions. Let’s focus on the clock in the next chapter to save you some brain pain by using those terms mentioned above as a way to picture cat evolution and much more.

Whee! (Image: M. Lellouch/NPS, CC BY 2.0)

Featured image: Tobias Mandt, CC BY 2.0.

Sources:

Kitchener, A. C.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; and Yamaguchi, N. 2010. Felid form and function, in Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids, ed. Macdonald, D. W., and Loveridge, A. J., 83-106. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Turner, A., and M. Antón. 1997. The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives: An Illustrated Guide to Their Evolution and Natural History. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wright, M., and Walters, S. 1980. The Book of the Cat. New York: Summit Books.

2 thoughts on “To Make A Cat”